In this second part of a two-article series exploring how Moomin books comfort readers during modern-day crises, the discussion between the author and TED-talker Andri Snær Magnason and Mark Ellingham from Sort of Books continues.

If you missed the first article, you can read it here.

Fighting climate change with words

Sort of Books’ Mark Ellingham is the UK publisher for both Tove Jansson’s and Andri Snær Magnason’s books. He sees similarities between the two authors since they both master the technique of dealing with big and complicated issues through storytelling. It’s the story that captures people’s attention, whether you write an allegory for climate change or war.

“It’s all about stories, isn’t it? And it’s the root of all Tove’s work and all your work, Andri – both in your adult and children’s books. And climate change is the heart of what you want to tell stories about”, Ellingham explains.

Andri Snær Magnason writes about environmental disasters and climate change in his own works of fiction. His first children’s book, the award-winning The Story of the Blue Planet, has been translated into some 40 languages, and his later narrative non-fiction novel On time and water, is approaching the same numbers. He has also done a popular TED-talk.

Magnason remembers meeting a scientist back in the day, who suggested he should write about climate change.

“And I said, ‘I don’t feel I have authority – I’m not a scientist, I don’t have the data. But the scientist said, ‘I’m not a storyteller, and people don’t understand data, they understand stories.´ So I started to think. What kind of stories can you tell that make climate science relatable? And what stories connect to us?

“people don’t understand data, they understand stories.”

Andri Snær Magnason wants to influence policy through his writing and brings up his book On time and water as an example.

“I’m trying to prevent the oceans from rising. So you’re suddenly in this kind of magical situation with artists that are writing about this issue – we’re trying to prevent the flood with words.”

Dance while you can – the Moomins take on threats and crises

Magnason and Ellingham pinpoint how Tove Jansson guides her readers through threats and uncertainty in her two first Moomin books.

“Tove Jansson was writing stories within very turbulent times, and she’s a very good example of how you react to, basically, apocalypse. She was even thinking of the megatrend we’re seeing now, with people not wanting to have children because of the future. Why should you have children just to be thrown into some chaos or the war machine, or in our case – the climate struggle?, Ellingham says, and continues:

“When you look at ‘The Moomins and the Great Flood’, it’s rooted in images of refugees and disasters. And in ‘Comet in Moominland’, even more so, you’ve got the whole cast of characters who are fleeing what they think might be the end of the world. To me, it’s about refugees. It’s about being reunited with family, which is a big theme in many of the books, isn’t it?”

“And now we have the climate crisis, and I was actually thinking of how her books fit the climate crisis”, Magnason says.

“It’s the humanity of “everybody is welcome”. It’s astonishing to read a book from that time where there’s almost no evil, apart from some tricksters and gloominess and some very dark figures. I think that is the big light that you can feel in her work.”

“‘Is this the end of the world?’ Little My asked curiously.

‘That’s the very least,’ replied the Mymble’s daughter. ‘Try to be good now if you can find the time, because in a little while we’re all going to heaven.’

‘Heaven?’ asked Little My. ‘Do we have to? And how does one get down again?’”

– Tove Jansson, Moominsummer Madness (originally published in 1954)

Mark Ellingham sees the same themes in Moominsummer Madness, where the end of the world seems to be near again in the shape of another flood, as well as the short story The Invisible Child (In Tales from Moominvalley, originally published in 1962) in which a maltreated girl slowly becomes visible again through the care of the Moomin family.

“Moominsummer Madness has catastrophe at its heart, but it’s a much lighter heart. It’s a later book – it’s written eight or ten years after the war. And it’s a comedy, really, and also has Tove’s great love of theatre at the heart of it. Well, one of my favourite bits in it is the part with Little My who asks how you can get out of heaven – I think that it shows just how the whole tone is different”, Ellingham says.

“Tove is a great example, because she’s living within the catastrophe. And if you look at images from Europe from that time, it is basically some kind of an apocalypse that is happening there. For me and for many people what you can learn from it is her philosophical point of view that even within the darkest moments, the most grave situations, she finds so much humanity and hope and and philosophy”, Magnason continues.

“it is her philosophical point of view that even within the darkest moments, the most grave situations, she finds so much humanity and hope and and philosophy.”

Tove Jansson writing for children and the child within

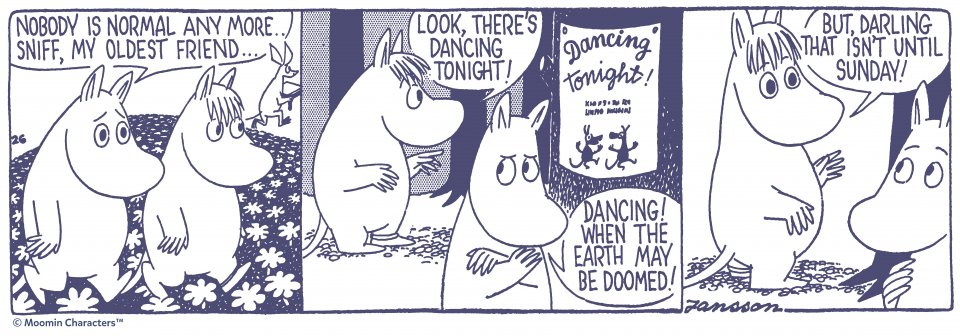

Magnason highlights a passage from the Moomin stories, which in English can be found in the comic Moomin and the Comet (1958) by Tove and her brother Lars Jansson:

Snorkmaiden wants to dance, but Moomintroll is reluctant – how could the possibly dance when the Earth might be doomed? Whereby Snorkmaiden replies “But darling, that isn’t until Sunday”.

…A fun fact for devoted fans: This passage is also included in the updated Swedish version of the Comet book from 1968 – ‘Kometen kommer’. Tove rewrote the original version of the novel, ‘Kometjakten’, ( from 1946) and added this passage in the rewritten version from 1968, but the English translation is based on this earlier version of the book – thus the dancing part is missing.

“There’s some kind of playfulness and joy. Personally, as an artist, I think her legacy is extremely important in children’s culture or fantasy children’s literature with these double layers, where you both talk to the children, but you also talk to the grown-up reading for the child or the child within every single grown-up. I don’t think Tove ever made a sort of obvious distinction between writing for children and writing for adults. She just told stories. Her books, like the Summer Book, for example, it’s impossible to say whether that’s a children’s book or an adult’s book”, Magnason says.

“I ask you, dear reader, isn’t it easy enough to be brave if you’re not afraid?”

– Moominpappa, The Memoirs of Moominpappa by Tove Jansson (original publication in 1950)

According to publisher Mark Ellingham, children’s writers often tackle bigger ideas than adult fiction writers – an opinion shared by Andri Snær Magnason.

“Yes, and they also take you, maybe for the first time, through certain journeys into joy, sorrow and fear. It might be the first time you’re encountering some of these feelings and issues in words, with some kind of context – and you’re guided through all this. I think that a good children’s book probably is one of the most important things you can do as an artist”, author and activist Andri Snær Magnason concludes.

Watch the whole discussion from the Reykjavik Tove Festival 2022 here:

Find a list of other articles related to Moomin books and how they comfort readers around the world in the first part of the article series here.

Mamma will know what to do – How Moomin books comfort us in times of crises, part 1

The first blog of a two-part series, this blog explores how the Moomin books comfort us in times of crises, decades after their creation.

The Källskär painting – the only Moomin-themed painting by Tove Jansson

The mini documentary “Wild Cliffs” tells the fascinating story behind the Källskär painting, the only Moomin-themed painting by Tove Jansson.

Follow Moomin Official on these channels

Check out the most important links for Moomin content and news, and follow Moomin Official on all major social media channels.