By

The Moomins, a family of trolls living in a valley with other colourful characters, have been beloved in their home country of Finland since the famed artist Tove Jansson published her first book featuring these characters in 1945. The stories have been translated into 50 different languages, and inspired multiple film and TV adaptations. But the Moomins have found a second home in Japan since the initial translations and an anime series loosely based on the originals were released in the late-1960s. Japan has historically accounted for around 30-40% of annual revenues for Moomin Characters Ltd., the company that owns the rights and licenses the original artwork.

But the popularity of Moomins has been rejuvenated in Japan and grown rapidly other Asian markets since around 2008, leading to explosive growth in sales of Moomin books and related goods. For example, the retail value of the Moomins in China grew by 300% in the past year. Interestingly, these trajectories were triggered by a move away from “cute” and a return to the original art and literature roots.

Hyung-Gu Lynn, the Editor of Asia Pacific Memo, sat down with Roleff Kråkström, the Managing Director of Moomin Characters Ltd. to discuss some of the details of the renaissance of the Moomins in Japan and their rapid ascendance in other Asian markets.

An Asia Pacific Memo interview with Roleff Kråkström

Hyung-Gu Lynn (HGL): Could you tell us what the current market share of Japan for the annual revenues of Moomin Characters Ltd. is?

Roleff Kråkström (RK): Since a period in the 1990s when Japan accounted for around 30%, it has risen to 50%. More specifically, the global annual retail value of Moomins is around 600-700 million euros, and Japan accounts for around 300-350 million. Finland accounts for a little less than 20% but of course has a much smaller population, although a fair number of our licensees are based here.

Moomin Characters office in Helsinki, Finland

(Credit: Hyung-Gu Lynn)

HGL: Could you share with us some of the thinking behind your decision in the mid-2000s to anchor all depictions of the Moomins back to Tove Jansson’s original artwork?

RK: When we had meetings with various licensees, they would invariably ask us whether we had any new film or television series in the works, or perhaps a monster app. This was a time when Angry Birds and other popular apps had just been launched. The answer to these questions was that no, we did not have such plans. The licensing industry is based on invention of content and control of distribution. Large entities such as Disney can produce at a specific pulse, where new products flood the market, and the wave lasts for say twelve to twenty-four months, then this is replaced by the next set of products. We fully respect what such companies do and appreciate that many people enjoy the products. But we also realized that we did not have the resources to compete with such giants in manufacturing entertainment.

We were thus forced us to ask ourselves – what makes the Moomins and our company unique? The answer was – art. We controlled a body of world-class literature and pictorial art that was licensable.

We wanted to be true to the original stories and the artwork without being protectors of some ossified heritage that operated on the basis of simply saying no to anything new. In other words, we wanted to work with the most talented people in various artistic fields without being overly aggressive about licensing new styles or new storylines merely to increase the volume of output.

We were fortunate in two respects. First, as a small company, we were and are able to make decisions very quickly while assessing proposals for quality and fit. Second, many artists came to us of their own volition to work with us, without us having to commission work. This stemmed in large part from the fact that the original Moomin stories contain all the universal values that any brand could dream of having. Aside from the heraldic imagery and storylines filled with adventure and pensiveness, you can find in Tove Jansson’s works love, family, adventure, bravery, tolerance, and loyalty. We didn’t have to fabricate these resonances.

HGL: What were some of the specific steps you took to persuade your Japanese licensees that the new policy would be beneficial? Given the large revenues from the various Japanese TV anime series versions, the shift must have been alarming for many of them.

RK: We actually implemented the new strategy in phases. Our Creative Director Sophia Jansson had been quite concerned about some of the ways in which the original Moomins had become diluted by some loose depictions. So we first started in the Nordic countries, where many of our licensees shared our concerns. Predictably, there was a mixed reaction: some of our partners were happy, while others were very worried. But we were able to run several successful projects with designers in these countries before applying the same policies to Japan.

In Japan, there was a cluster of steps. Our agent in Japan, Tuttle-Mori, had some merchandizing agreements with third parties. First, we discontinued these. Second, the new companies hired by Tuttle-Mori came in with a blank slate. Third, Mr. Takumi Nakayama, who had worked at Disney for many years, joined Tuttle-Mori as a licensing director and was instrumental in hiring staff and designers who were very receptive to our vision. Clear communication and persuasion are of course important, but to land a strategy like this unavoidably requires some changes in partners or third party licensees.

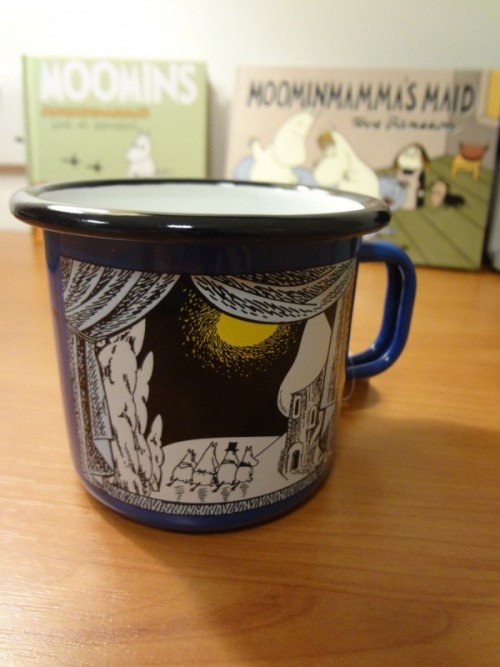

Moomin mug and books

(Credit: Hyung-Gu Lynn)

HGL: In Japan, some of the character names have been changed from the original works. For example, Hattifatteners are widely known as Nyoronyoro and Snorkmaiden as Non-non. What is your position on these indigenized names?

Indigenizing names is common in translations of literature, since the translations need to be true to the original but also coherent to specific cultural contexts. Simply put, as owners of a body of literature and art, we have no objections to the indigenization or localization of character names.

HGL: Moomin Cafes have been operating since 2003 in Japan. Can you explain the licensing agreement for the Moomin Cafes? And how do you account for their recent popularity in Japan and other countries in Asia (one opened in Hong Kong in 2014, another is scheduled to open in Bangkok in 2016)?

RK: We don’t make products such as china or blankets, or run cafes ourselves. The Japanese firm Benilec operates the Moomin cafes in and outside of Japan under license. I think people very much commit to the values contained in original art. For example, one of the reasons you might buy a book is paradoxically because you have already read it. This is the social element of consuming art or books – you want to communicate to family, friends, colleagues, and others that you share the values embodied in a particular work. Generic products or characters do not have similar value propositions. So in Japan the Moomins have been read by three generations who find comfort in re-engaging with the core values and communicating this commitment to others. By visiting a Moomin Café, whether in Tokyo, Fukuoka, or Hong Kong, you are partaking in this social element of consuming art and literature.

Moomin bakery & cafe Tokyo Dome City Laqua

(Credit: Benelic)

HGL: Could you elaborate further on what you see as the dynamics fuelling the rise in the popularity of the Moomins in other East Asian markets such as Taiwan, South Korea, and China?

RK: First and most importantly, as we’ve discussed, we definitely see literature and art appealing to educated consumers who embrace the values in the original works, which might be particularly appealing in times of rapid socio-economic change. More than other licensable art or properties, there is a way in which Tove Jansson’s stories present a new package of values or even a roadmap for happiness, if you like, to readers. Specific characters or events are not just popular in and of themselves but as emblems of other values. Snufkin’s seasonal travels or Moominpapa finding a bottle of whisky on the seashore represent the allure of travel and adventure, of the joys of experiencing new people and places across the sea. So a reader in say China does not have to know about the specific history of alcohol prohibition in the Finland in the 1920s and the mystique of bottles from other countries washing up on the shores of the islands in the Archipelago Sea where Tove Jansson lived, to appreciate the romantic symbolism of Moominpapa’s bottle.

A second, more technical factor is omni-commerce, the use of multiple channels such as digital and physical retail to generate a contents-based experience for and interaction with customers. Even just a couple of years ago, our web page was rather static. Now, the official web portal has helped expand reach and provided a template that can be applied to various countries. Around 95% of the content in the official Japanese web site is translated from the main version. Fans and bloggers provide much of the content, although we moderate it. Our Japanese partners then translate it, while the rest is locally produced content. We have applied the same template to China and South Korea, and also opened a physical Moomin Shop in Seoul in 2015.

Moominworld in Naantali, Finland

(Credit: Hyung-Gu Lynn)

Text and photos by ASIA PACIFIC MEMO